Spring 2020. Working from home, board game nights canceled, rec centre closed, no commute, no social activities. New free time. As the sun set later, I rambled further into the hills on my walks with Poe.

I listened to podcasts at first. The Omnibus, Radiolab, How to Save a Planet. By the new year I had sifted the archives of episodes that interested me, and was ready for something else. Sabrina told me to get Libby. That was in February 2021, nearly 300 hundred plays, novels, epic poems and short story collections ago.

Frequent Authors

This is very unfair. I would have liked more Eliot, Woolf, Faulkner, Dostoevsky, and a lot less Galsworthy. Ann Radcliffe is completely absent despite my repeated searches. This is just what my libraries have in English audiobooks. Another reason for this distribution is that I’m going through these books in a vaguely oldest-to-newest order. The further back in time, the more dominated by white men.

| Author | Number of Titles | Median Rating | Favourite |

| William Shakespeare | 38 | 6 | Hamlet 9/10 |

| John Galsworthy | 11 | 6 | Flowering Wilderness 7/10 |

| Thomas Hardy | 9 | 7 | Far from the Madding Crowd 8/10 |

| Oscar Wilde | 9 | 6 | The Importance of Being Earnest 8/10 |

| Laura Ingalls Wilder | 9 | 6 | These Happy Golden Years 7/10 |

| Lucy Maud Montgomery | 8 | 7 | Anne of Green Gables 8/10 |

| Mark Twain | 8 | 7 | A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court 7/10 |

| George Bernard Shaw | 8 | 6 | Pygmalion 7/10 |

| Jane Austen | 7 | 7 | Northanger Abbey 8/10 |

| Earnest Hemingway | 6 | 7 | The Old Man and the Sea 8/10 |

| Fyodor Dostoevsky | 5 | 8 | Crime and Punishment 8/10 |

| Leo Tolstoy | 5 | 8 | Anna Karenina 9/10 |

| George Eliot | 5 | 8 | Silas Marner 8/10 |

| Elizabeth Gaskel | 5 | 7 | Wives and Daughters 8/10 |

| E. M. Forster | 5 | 7 | A Passage to India 8/10 |

| Edith Wharton | 5 | 7 | The House of Mirth 8/10 |

| Rudyard Kipling | 5 | 7 | Kim 7/10 |

| Louisa May Alcott | 5 | 6 | Turbulent Tales 8/10 |

| The Brontës | 4 | 8 | Wuthering Heights 9/10 |

| Pearl S. Buck | 3 | 8 | The Good Earth 8/10 |

| William Faulkner | 3 | 8 | The Sound and the Fury 8/10 |

| Virginia Woolf | 3 | 8 | A Room of One’s Own 8/10 |

| Liu Cixin | 3 | 8 | The Dark Forest 8/10 |

| Herman Hesse | 3 | 7 | Steppenwolf 8/10 |

| James Joyce | 3 | 6 | Dubliners 7/10 |

| Anthony Trollope | 3 | 6 | The Way We Live Now 7/10 |

| Wilkie Collins | 3 | 6 | The Woman in White 7/10 |

| W. Somerset Maughan | 3 | 5 | Of Human Bondage 6/10 |

| Anton Chekhov | 3 | 4 | The Three Sisters 5/10 |

Libby is just Audible but for the library, so if you have a library card, you can borrow from the catalogue of audiobooks and ebooks. It’s incredible. I linked my old Ottawa and Sudbury cards and my parents’ Edmonton one.

This is my first experience with audiobooks and it felt like cheating. That feeling revealed something I didn’t like to admit: that I don’t always read because I enjoy it, rather because I think of myself as a reader and need to prove it. But I haven’t read all that many books since university. Every year, the internet takes more and more of my attention.

At some point I came to realise that there are more – many more – great books than can be read in a lifetime, even if 80% of my reading hadn’t gradually migrated to a computer screen. I felt guilty about this, and guilty about my bookshelves, something that used to be a source of comfort and pride.

Listening to Shakespeare seemed justified. When would I realistically ever read his 3rd tier plays? Besides, his plays weren’t meant to be read. They ought to be performed, so audio books seem more appropriate anyway. This logic helped get me started, and it held for oral epics like The Odyssey, The Canterbury Tales, and Beowulf. By the time I had finished these, it was early summer, I was over the snobbery, fully enjoying the stories.

The walks refilled me. The exercise, the companionship of my dog, the forest, the flood of language and ideas – all of it gave me energy. I didn’t like every book, but I loved enough of them. Some I might never have read any other way.

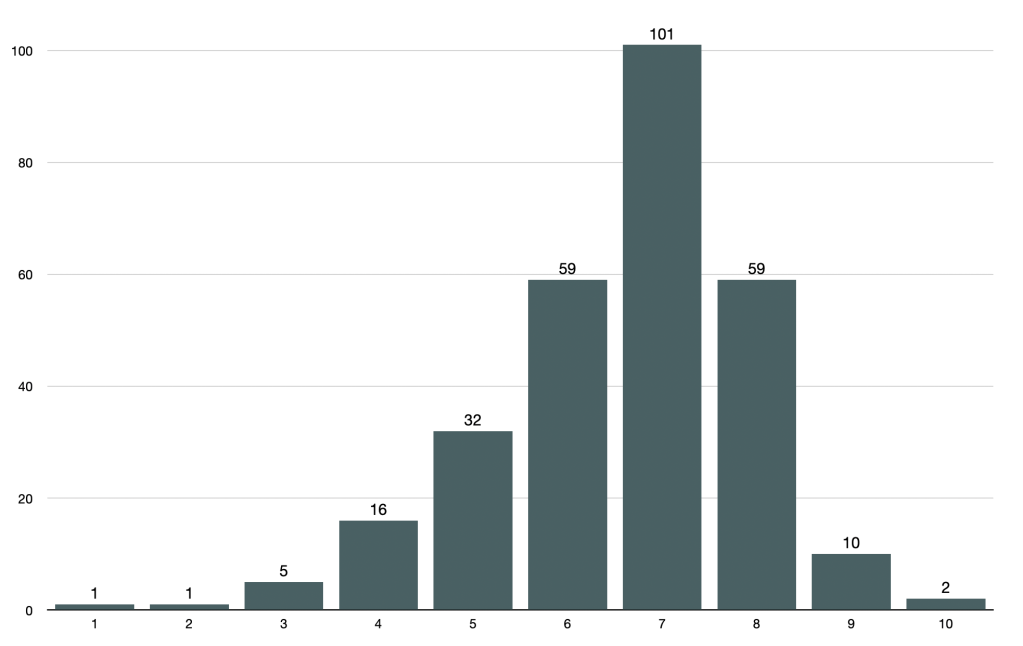

Eventually I started keeping a list with a rating. Here are my favourites. I don’t really know what the ratings mean. Maybe just how glad I am to have read them. They are subjective, and while I’ve tried to be honest, I’m probably fooling myself and letting fame tip the scales here and there.

Top 50

- Beowulf Translated by Maria Dahvana Headley 10/10

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky 10/10

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy 9/10

- The Trial by Franz Kafka 9/10

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy 9/10

- Hamlet by William Shakepeare 9/10

- The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky 9/10

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë 9/10

- Othello by William Shakepeare 9/10

- Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier 9/10

- Macbeth by William Shakepeare 9/10

- Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy 9/10

- Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 9/10

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë 8/10

- Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray 8/10

- Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome 8/10

- The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 8/10

- The Old Man and the Sea by Earnest Hemingway 8/10

- The Cossacks by Leo Tolstoy 8/10

- Twelfth Night by William Shakepeare 8/10

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes 8/10

- Silas Marner by George Eliot 8/10

- King Lear by William Shakepeare 8/10

- Wives and Daughters by Elizabeth Gaskell 8/10

- The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot 8/10

- The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy 8/10

- The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank 8/10

- Under the Greenwood Tree by Thomas Hardy 8/10

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde 8/10

- Much Ado about Nothing by William Shakepeare 8/10

- Paradise Lost by John Milton 8/10

- Gilgamesh Translated by Stephen Mitchell 8/10

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë 8/10

- Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen 8/10

- Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol 8/10

- The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner 8/10

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen 8/10

- A Passage to India by E. M. Forster 8/10

- The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton 8/10

- An Immense World by Ed Yong 8/10

- Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery 8/10

- A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf 8/10

- The Ugly Duckling et al. by Hans Christian Andersen 8/10

- The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster 8/10

- Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy 8/10

- The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald 8/10

- To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf 8/10

- The Order of Time by Carlo Rovelli 8/10

- A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen 8/10

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (Dramatized) by Oscar Wilde 8/10

The Start

February 10, 2021

The end of January brought a brutal cold snap. Winter crawled down from its seat in the arctic and seeped over the prairies. For two weeks the air hurt to breathe and I hardly stirred from our cozy little house. But winter could not hold back the jet stream forever. The warm Pacific air broke through, as it always does, and rushing through the teeth of the Rocky Mountains, it drove winter out of our valley. On February 10th, I downloaded my first audiobook, leashed an overjoyed Poe, and started to explore.

It was icy and dark and I rarely walked for more than an hour. I went slowly until I found my footing. I wasn’t used to listening to audio books. These first few were part of a series called Shakespeare Appreciated, popular in high schools. They were training wheels for me. If my attention wavered for too long and I lost the thread, I was always saved by Joanne Walker’s helpful interjections. They were always enthusiastic; never condescending. After listening through with the notes, I re-listened to the play without, and could enjoy it even more.

Othello 9/10

Of the great 4 tragedies, this was the one I hadn’t yet read. Iago is a magnetic personality. It’s a pleasure to see a truly competent person doing something at the highest level, and for Iago, that is lying. Having Shakespeare write your lines will make most characters sound clever, but it feels like the playwright is putting forth all of his powers to conjure convincing proofs out of empty words.

The play is called Othello, but it’s all about Iago. All the other characters are caught up in his schemes, their futures deflected by the words he whispers in another’s ear. Who is he? Just an uncommonly wicked and skillful dissembler, or the Devil himself? The ingenuity he shows in manipulating Roderigo and Othello, and the cold blooded murder of Cassio feels almost supernatural. But then the way he is simply and suddenly undone by his wife, who has presumably survived years of marriage to this monster And kept her morality intact, points to a very common foible: underestimating women.

Throughout the play we get an ugly glimpse of Iago’s contempt for the other sex. Like all liars, he doesn’t believe anyone else is honest. This double blind spot leads to his downfall in one perfect moment.

I listened for “problematic” tones since it deals with race and is over 400 years old. Yes, some of the minor characters throw jealous slurs at Othello, and the villain Iago uses a stereotype about Moors to try to sway another character, but I never felt like Shakespeare believes it, or is inviting his audience to such views.

Julius Caesar 6/10

Remarkable for the rhetorical battle in the middle of the play between Brutus and Marc Antony. No doubt political speech writers have for centuries been mining these speeches for techniques. Also interesting is the falling out between the conspirators as the people turn on them. The end is a bit tedious and Caesar himself is a flat, dull character who, happily, doesn’t make much of an appearance in his own play.

Twelfth Night 8/10

A real surprise and delight! It starts funny with the melodramatic and downright emo Duke Orsino. Fun for Olivia to fall in love with Viola. The famous Shakespearean gender bending of men playing women playing men comes off well here, and I believe I detected a winking attitude towards homosexuality, from the subtle (the Duke pouncing on Viola as soon as society permits it after secretly being attracted to her in thr guise of a manservant), to the explicit (the sea captain playing sugar daddy to a reluctant Sebastian).

This play would be merely enjoyable, but the Malvolio subplot pushes this into the ranks of elite Shakespeare for me. Malvoleo is a great parody of me, well read and confusing the clever passages he can quote for his own wit. Add in self importance without any self awareness, and the come-upance feels justified, even though it is pretty harsh. The Sir Topas bit is such a rich gold mine. Feste is my introduction to a top tier fool, and is the ideal foil for Malvoleo – no ego, but real brains.

In Stride

March 9

The library didn’t keep Shakespeare Appreciated in stock. A couple months after I started, they had disappeared and I had to pick through the various productions unaided. The BBC versions were uniformly excellent. The American theatre companies are more hit or miss.

At this time I decided to make a run at Shakespeare’s complete canon. It went quickly by then. I could often finish a play in one long walk or session on my climbing wall. The longer days drew me out further afield and the little feeling of accomplishment from completing books and discovering new paths in the hills converted this new practice from an experiment into a pleasurable routine.

King Lear 8/10

Half-remembered from high school English, this surprised me with how dark it is. Act I; Scene I: a fragile king commits his fatal blunder. Cordelia banished. His snakey children Edmund, Goneril and Regan plot against the remaining good guys and when it seems none are left, betray each other. There’s hardly a glimmer of salvation in the end as the returning heroine is swiftly captured and executed and Lear dies of that terribly common affliction, a broken heart.

Among all this evil, the rays of light, Cordelia, Kent, and Edward, are profound and memorable. Cordelia’s speech at the beginning, that so incenses Lear, is a surprising one from Shakespeare, who you’d think would be the last to deny the power of language to express love. Her sacrifice at the end ransoms the king’s mind, and though he dies miserable and undeserving of her, he sees the truth at last.

Even more astonishing is how Edgar behaves, at first simply naively out of his own goodness. But then Kent reduces himself to the position of servant to help the king he loves, and Edgar outdoes him by descending still further into obscurity after he and Lear are driven into the wilderness. To comfort his mad king, he willingly dons insanity himself, and, still as in the disguise of Poor Tom, works to save his blind and despairing father. Also, he kills Edmund, so there’s at least one thing we can feel good about in this play.

The Tempest 7/10

A nice palate cleanser after Lear. The good guys win, we get some proper wizardry, and the bad guys clown around. Caliban is a bit uncomfortable. Is he meant to be a “savage native” caricature? I’d be more interested in him if he was written sympathetically but it seems like we’re told he tried to rape Miranda and so we have permission to laugh at his woes. I read it in university and enjoyed it about as much as this revisit.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4/10

The arbitrary switching of who loves who quickly gets tiresome. I just don’t like any of the characters or believe in any of their motivations. The only bright spot is the theatre troupe. I’m a sucker for the bad acting bit. Always tickles me.

Romeo and Juliet 6/10

The prettiest language in all Shakespeare is paired with the most infuriating plot and the dumbest characters. Everyone just keeps making the foolish possible decisions from beginning to end. But the glittering speeches dazzle the ear and we don’t mind so much.

Can we talk about Friar Lawrence? Why is he such a meddler? He’s giving love advice, he’s working behind the scenes to solve political disputes, he’s secretly performing marriages, and he’s concocting wild schemes to fake a death using magical herbs. Is this his day job? Does he freelance these services to all who ask? Now, one of those Italian renaissance noblemen or maybe a cardinal I could see, but a humble friar up to his eyes in intrigue? Just bizarre.

Hamlet 9/10

This one has atmosphere. Ghosts and madness, banter with the skull of a jester, and a great many murders. We get not one but three different methods of poisoning but the most baroque has to be pouring poison into the ear of a sleeping king. What a metaphor. I find that I’m just listing stuff I loved in no particular order, so while I’m at it, one more: fighting literally inside the grave of the innocent Ophelia.

Hamlet himself is a tremendous anti-hero. Both brilliant and crazy and where does he find the energy? Unsurprisingly, given all the things I’ve mentioned and the many more I’ve omitted, the play is long. You could argue it’s too long. I wouldn’t complain if the whole bit about going off to England and getting captured by pirates was cut. Seems like a 5th wheel to me. I would not hear of cutting the play within the play, however. First of all, Shakespeare has a lot of fun ideas about the theatre, and second, it’s a wonderful bit of psychological tension.

I would read a short story from the point of view of the players. This manic prince is giving us a million directorial notes, clearly another courtier who secretly wants to be an actor himself, though this one might have some talent. The scene he orders is NOT going to play well but he’s the one paying us, so he’s the boss.

Henry V 6/10

This is the “band of brothers” play. Henry V has become a model of leadership. Courageous and inspiring. The Chorus extols his nobility and virtue. But war is not good, and this gilt English propaganda can’t fully coat what is underneath: the cruelty and thirst for blood necessary to prosecute a war of offense. I don’t think Shakespeare is subtly critiquing Henry or the English attack. I think that is projecting our modern values and giving him way too much credit.

There is some pretty language and strong speeches. I like the scenes with the common people. They are clear eyed and cynical and provide a bitter dose of realism to a play otherwise full of jingoism about good old England. But mostly it’s a 500 year old superhero movie. It’s simple and childish. The good guys are brave and win against all odds and they are gracious in victory and they are in the right because of course they are.

All’s Well that Ends Well 5/10

I’m of two minds on this one. The plot is fun and ingenious, and I like the resourcefulness of the heroine, but it’s just impossible to believe that any woman would try so hard to marry a thoroughly rotten man like Bertram. He humiliates her in court, he lies to everyone, he is sleeping around, and only agrees to marry her on penalty of death. All is not well at the end of the play, and I’m certain it will only get worse as the marriage goes on.

As You Like It 7/10

A merry romp full of wordplay and trickery. The characters are so cheerfully absurd – an exiled duke reigning in the forest, a court jester dragged along by an impetuous lady, a Very Strong Man, and my favourite, the lovesick gentleman and his truly awful poetry. There’s not a lot to chew on here, but it’s always lively and interesting.

Macbeth 9/10

We love a cackly witch with full on cauldrons and eyes of newt. We love that old world kind of prophecy where you can debate whether it would have come true if they hadn’t heard the prophecy. We love the waking nightmare that the MacBeths live in after the regicide that is capped off in wonderful style by a moving forest.

From the instant that Lady Macbeth turns her husband, every scene is on a tightrope. The dread and tension are sustained until the last act when we are finally given a full resolution, simpler and more satisfying than in Lear.

Almost a year later and I’ll admit I can’t remember which one was Duncan and which Malcolm but I do remember the mood of psychological horror. It’s the Tell-Tale Heart by Poe. It’s a shadow creeping up the stairs.

The Merchant of Venice 4/10

If the only thing you know about this play is the “if you prick us” speech, then you might think that Shakespeare was making a powerful case for racial equality. That is not how the rest of the play goes. Shakespeare plays Christians taunting Jews for laughs, and of course in the end, Shylock is tricked and doomed and this is portrayed as a happy ending.

There is a tacit admission throughout the play that the Christian domination of Jews is not altogether just, so I don’t think this is a simple case of pure anti-semetism like Oliver Twist. But on balance I have to dock a lot of points. It’s a shame because there are other praiseworthy parts of the play. Portia’s speech about mercy blessing both the giver and receiver is powerful, for example.

Intermission

April 3

Warm sun. Thin drifts of old snow, speckled with fallen needles. The understory is still dormant. This is the time of year that is easiest to follow game trails. A break from the bard provides an inner change to herald the new season.

The Odyssey 6/10

Oh, that rosy-fingered dawn and wine-dark sea. Had this not been narrated by the extremely capable Ian McKellen, this might have become tedious. It really is just one damn thing after another, but enough of the adventures are stories worth telling.

There is, charitably, just a touch of character development – sometimes the heroes are sad, for example. But this is Greek myth, where that sort of thing isn’t done. Each character has one trait (our hero Odysseus is “crafty”) and that will have to do them for their entire lives. If you want more , don’t look for a character to develop them, just add another character. By comparison, this is miles better than The Iliad. At least with The Odyssey we get a lot of new scenery.

Life’s Edge 7/10

In grade six we memorised the characteristics of life. If something ticked all the boxes, it was alive. Simple. It wasn’t until first year university that I started to appreciate the full messiness of nature. There are gradients to everything. When a species evolves into another, where exactly do you draw the line? Are quorum-sensing bacteria multicellular? Are viruses alive?

Nature doesn’t come with any categories. It just exists in all it’s chaotic glory and any attempts to systematise it to make it knowable is doomed to be incomplete at best and generally just wrong.

It’s a great premise for a book. Zimmer pokes at the concept of life from a few different angles – biogenesis, our intuition about viruses, and organoids grown in a lab. He puts on different definitions of life and notices things about the world that just don’t seem to fit right with any of them. It’s like trying to dress an octopus with the clothes in your closet.

Histories

April 15

In Canada, spring is merely a series of brief winter remissions that come and go March through June. First spring, second spring, fool’s spring, the slushening… Meteorologists estimate that there are 39 in total, same as the number of Shakespeare plays. The unwary will often think winter is dead at last, only to wake up to yet another April snowstorm.

Likewise, it was around here that I started realising first, just how many plays Shakespeare wrote, and second, why I had never heard of most of them. Many are just plain boring. Others have passages of clever language or a few interesting characters but I can’t say are worth the effort either as entertainment or history.

Henry IV Part 1 7/10

Falstaff is one of the great sinners of literature. The bawdy tavern scenes are such a contrast with the anxious meetings of Bolingbroke and his advisers, and so much more enjoyable, that it almost feels like a criticism of courtly behaviour. It’s somehow good to be reminded that audiences in the 1600s revelled in cheeky indiscretion much as today.

Compared to John and Richard II, this brings human-scale action. In those plays, the plot was entirely devoted to affairs of state and lofty speeches about abstract ideas regarding divine right. This being a history of a king (in name, anyway), there are some political scenes, but even those are brimming with personality. Glendower is a petty blowhard haggling over land while trying to intimidate the other lords by claiming to be some kind of Merlin-esque figure. Hotspur is as described on the tin, but with a strong noble side. Henry Bolingbroke, ostensibly the main character though he takes a back seat to his son, is harassed but competent, and the climax of the whole book is his emotional meeting with his son. Shakespeare, clearly fond of him, gives that son a fine redemption arc, taking him from loveable scamp to serious hero.

It’s a good mix of action, comedy, and feeling.

Henry IV Part 2 6/10

Kind of a sixth act to the last play. Not too much happens that would be of interest to historians, but the gap in content is easily filled by the girth of Falstaff. The title character does even less, but his scenes are emotionally interesting. He can’t seem to escape recollections of Richard II, and, beset by worries, he seems to fear that his fate will be the same. It’s not quite guilt, but perhaps a little bit of remorse. He is also estranged of his son, unable to make up his mind. His suspicious mind sees fault and treachery, but in the end he cannot deny his father’s heart.

Hal’s speech to his dying father struck me for its elegance and recalled the lawyerly skill of Iago, if Iago was explaining an honest mistake for once. I don’t believe the transition he makes. It seems too abrupt. Maybe the head that wears the crown truly is weighed down with cares.

Falstaff is probably the weakest part, just because he is in more of the play than he warrants. He’s amusing and awful and outrageous, but it’s just slapstick. It works better to have a fool that appears and disappears a regular brief intervals instead of commanding entire acts.

Cymbeline 5/10

This might be the most complicated play of all. The wicked stepmother tricks a servant into thinking poison is medicine but she was also tricked and it’s really a sleeping potion. There are long lost twin brothers and the princess Imogen dresses as a man and the rake Iachimo fails to seduce Imogen but succeeds in tricking Imogen’s lover into thinking she is unfaithful. You could say there are a lot of twists. The problem is that not all of them seem motivated. Why did Belarius give the king his sons back after all this time? Why did The king refuse to pay tribute and then pay it after winning the battle? And so on.

The Comedy of Errors 5/10

This play probably pushes the mistaken identity plot device the furthest of any in the canon, and in such rapid fire madcap style that it’s dizzying. The result is at first amusing and then just tiresome. It’s the same joke told over and over for no increase in the payoff.

Henry VI Part 1 5/10

Full disclosure: I almost instantly forgot what happened in which Henry VI. On a second listen, I’m startled to discover that this play has Joan d’Arc. Ah yes, scene after scene where some random nobleman is announced, says something stentorian, and then rushes off. It comes back with all the pleasure of stepping in something wet in the night. On top of a litany of squabbling Dukes, there were also Earls and Lords, none of whom I managed to keep track of. A passionate student of British history may have an easier time and find some enjoyment.

Somewhere in Act IV, the writing started to get a lot better. The speeches became a lot stronger. They started to talk in more heroic couplets, there was suddenly an emotional component to what used to just be stale exclamations, and a little irony. It’s not enough to recommend the play. The characters are mostly still just walking names from a history book, and I didn’t really like how they did Joan at the end.

Henry VI Part 2 6/10

The writing is Shakespearean from the start this time, and the characters have a bit of juice to them. This helps a lot in keeping all the noblemen straight, but it’s not enough. There are simply far too many, and even on a second listen, I kept losing track. I appreciate that there are some weird plot points sprinkled in to break up the squabbling court scenes like the whole necromancy thing, but these soon stray into excess. Not only is the central plot about the political factions on the complicated side, there is also a love triangle, trial by combat, assassination, popular rebellion, trial civil war, and finally real civil war.

These are all fine side plots, but it makes the play over-long and distracted. Cade’s rebellion is the most substantial of them. I guess this is political satire, and it’s interesting that the feckless mob is lampooned for being swayed as easily as a feather with pretty basic sloganeering. It’s also interesting to see that promises of cheaper or free stuff, and an anti-literacy (anti-elite) platform was considered the dumb easy way for hacks to gain followers even back then.

The way the rebellion ends is similar to the Cardinal, and the King himself. Not with a bang, but weak and grovelling. But we’ll get to that in the next one.

Henry VI Part 3 5/10

This is the worst for being an endless procession of dukes swearing oaths and arguing and running around. Everyone seems to have just finished reading The Iliad because for some reason they keep forcing references into their speeches. The title king is so snivelling and spiritless that every scene with him tries our patience as much as his wife’s.

Speaking of, Queen Margaret is the most interesting character. Dauntless, ruthless, able to command armies if not her husband’s energies. She emasculates York and I suppose the glass ceiling was pretty strong back then, or else she would surely have ruled England and headed off the rebellion somewhere during the last play. The only other highlight is our introduction to the young Richard III, who gets a thoroughly gnashing soliloquy near the end.

Richard II 6/10

He’s doing this thing where the characters are not only distinguishable by the words they say, but also the rhythm and rhyming patterns they use to say them. Half the play is spoken by the usurpers and other minor characters in blank verse; the other half by Richard is in heroic couplets and sweeping metaphors. His lines sing, and I mostly enjoyed this play on those grounds. This is near the pinnacle of Shakespearean language. The other half is more ordinary but still effective.

It isn’t that Shakespeare seems to be particularly pro-Richard and anti-Henry. The nobles accuse Richard of waste and indecision and oppressive taxation and there is no word in his defence. No word, that is, besides “and yet I am king.” Is being a king about your birth or your actions? Shakespeare lets us decide the question.

My first impression was that none of the characters were all that interesting, the courtly scenes are stuffy and the much more interesting lower class scenes are entirely absent from this play. Certainly the plot would benefit by spending more time on the usurper. We know he can write a conflicted anti-hero. Instead, this play remains locked onto the title character as he makes a series of catastrophic decisions and nondecisions.

Richard III 7/10

Far and away the best of the histories. We get a delicious anti-hero for the protagonist. Cunning and ambitious, a honey-tongued villain. The audacity of the scene with Lady Anne is absolutely something else. Shakespeare seems to be arguing that if only you can be eloquent enough, words are the strongest force in the universe: greater than reason, love, and hate. He of all people ought to know.

I don’t know what the politics of the time were, but I wish Shakespeare had always been as fearless in making his monarchs into such juicy characters. And he isn’t the only one. I also loved the profanity-laced appearance of Queen Margaret who is the only one who sees Richard for who he is.

The actual plot is pretty dull. Richard simply murders everyone, one after the other, until the entire country is disgusted with him and kills him back. It’s like the evil Romeo and Juliet where all of Shakespeare’s immense powers are bent on expressing deceit and wickedness instead of love, and this greatness is let down by the plot and characters.

King John 5/10

Poor John can’t catch a break. The French are retaking his towns, the nobles are conspiring against him and the Pope sends over a delegation to excommunicate him. Then, to cap it all off, a tragi-comic misunderstanding frames him for the death of a rival claimant to the throne. You’d think it couldn’t get any worse, until a random monk poisons him. Fin. It’s almost slapstick.

The first half is honestly just boring. They argue about who is the rightful king, citing laws and justice and family trees. Nothing is more deadly dull than family trees. When the Cardinal shows up, there is at least a little bit more interest. John scorns the excommunication, calling it a curse lifted by money. Zing!

Henry VIII 4/10

Hooo boy was this dull. Shakespeare is at his best inventing characters from far away lands or in the distant past. There he has the freedom to make them as mean or as inscrutable or as flawed as he likes. I guess these people are too recent. Some in his audience may have lived in their time and especially among high society patrons, being on the fashionable side of history was vital. Being too critical or praiseworthy of anyone in Henry VIII’s court was dangerous. And the result is this insipid, half hearted mess.

Instead of a court scene where Buckingham is unfairly tried, we simply hear it told about afterwards. Instead of hearing how the King and Anne fell in love at the dance, we are simply told about it afterwards. Instead of a dramatic climax where Wolsey’s letters to the pope are intercepted and he is revealed to be a traitor, we are told about it afterwards. It’s always a couple anonymous gentlemen giving a synopsis of what happened, which I guess is safe because he won’t make descendants and allies of court figures mad by writing lines for the historical characters directly; all we get is what these gentlemen have heard happened. Well, it also robs the play of all its drama and interest.

The argument between Katherine and Wolsey is sort of interesting, but that’s about it. And the wild praise of Elizabeth at the end was beyond satire. Stick to fiction buddy!

True Spring

May 14

By the end of this set, we had put in our garden, set up the hammock and I had at last exhausted my libraries’ supply of Shakespeare. I’m not sure what seeds it planted in me, but I do believe something will grow from it one day or another.

By now I was hooked and even as I finished my tour of Shakespeare’s canon, I kept finding more books to borrow.

Antony and Cleopatra 4/10

I was quite disappointed with this one. I was still in the throes of passion for history, and the fame of this play so far outstrips nearly all the other recent ones that I was expecting something at least as good as Julius Caesar. Unfortunately, this turns out to have the same problems as Romeo and Juliet – the main characters are all abominably stupid and selfish – without the benefit of above average language.

Much Ado about Nothing 8/10

The other big surprise was how good this one was! I enjoyed spending time with all the main characters, especially Beatrice. They are lively and distinct, and that classic medieval baddie, the bastard prince, is just the right amount of wicked. The plot is a well-worn formula, but it’s effective and has some nice little surprises along the way.

The double courtship is, as mentioned, packed with witty repartee and delightful little setups. I learned later that the title is a very apt play on words: nothing was pronounced “noting” in Elizabethan times, which meant eavesdropping. The stakes are high by the climax when it looks like poor Hero has been ruined by the dastardly Don John, but her friends believe her and there is enough time left in the play to sort it all out.

However, we are alarmed to see the entrance of a friar who – oh dear – hatches a scheme for Hero to fake her death. This did not go well in Romeo and Juliet, we recall. But this is a cheerful play, with characters who are reasonable and willing to forgive and see the best in each other, and this time it does all work out. Though overmatched by both circumstances and their love interests, Claudio and Benedick do show their good natures in their end and we get a double wedding after all, happily ever after, the end.

The Sonnets (Shakespeare) 7/10

I really have no ear for poetry. I can’t find the right frame of mind to appreciate it apart from prose. But even brutally flattened into prose, there are many lovely phrases and clever ideas to enjoy. I thought they were surprisingly uneven in quality. I understand poets wrote sonnets on commission, essentially, for aristocrats to pass off as their own during courtships, and any artist who has to satisfy a client will know the pain of compromise. Maybe that is what happened in a few of these. Or maybe Shakespeare just had an off day.

The Canterbury Tales 7/10

I should have expected all the fart jokes, but happily, I didn’t. Most of the memorable stories are funny, often taking the form of one occupation chirping another. The millers and the carpenters seem to hold a particular animus for one another. Some other tales sound like legends. The knight’s tale has all the touchstones of an Arthurian sidequest.

There is duplication. We have a story about a good priest, and another about a bad one. There are some unfinished tales that the other characters cut off out of boredom, and the entire collection is probably incomplete as well. All of this is assembled haphazardly, as though a bartender wrote down the stories shouted by drunken customers in between rounds, by no means systematically.

It’s unpolished, it’s uneven, it’s bawdy, it’s lively, and the overall effect is charming.

The Taming of the Shrew 2/10

One of the few that I simply detested. Shakespeare shows us a charming, vivacious young woman and in scene after scene, has the “hero” starve, beat, and intimidate her until she is broken and subservient. It’s presented as a straightforward happily-ever-after. The jacket notes try to spin this as extremely subtle irony. No chance. This was popular entertainment, a comedy, playing to the sensibilities of an audience of drunken men who paid a penny for a funny show. It makes light of common cruelty and instructs the audience to follow this disgusting example.

Pericles 4/10

This is starts as a straightforward quest to marry a princess. Periclese sees the trap (incest!) and escapes. And then a completely new story starts. I never got a satisfying resolution to the first, and the second is a bit of a mess too. There is some good material here but it badly needs rearranging and trimming.

Three Sisters 5/10

This was effective at presenting (and imparting) a frustrated restlessness. A modern species of depression. I can’t say I took any pleasure in the story, but I appreciate the unity of theme and tone.

The Lady with the Dog 4/10

I have a similar complaint/compliment again. The characters and the world feels real, but it’s unpleasant. I remember my stay in Yalta and Moscow as being drab, cheerless, grey. It left me cold and listless.

The Skin We’re In 8/10

First person journalism. Injustice is witnessed and interpreted for privileged white Canadians like me. It tried to make me see what has been happening in my periphery all my life, unnoticed.

There is a reporter’s attention to facts, but also raw emotion. A human reaction against systematic cruelty.

Policing Black Lives 6/10

Precise, densely sourced, almost legalistic journalism. It reaches deep into the past, when slavery was practiced in Canada and draws lines throughthis land’s history to the present. It also makes a wide search of modern Canada, interrogating every institution and building a powerful case against each in turn.

The argument is that racism is pervasive in Canada. It is the air we breathe and the material of the state.

This book is most effective as a resource for explaining racism to white acquaintances. Filled with facts and examples, statistics and studies. As a cover to cover read, it is dry and can feel repetitive, though really just exhaustive.

Legends

June 13

Waiting to let Poe cool her paws in the creek, listening to Dante. Kneeling in the garden, pulling weeds, and picturing Satan slipping into another garden to tempt Eve. Long days and long legends, still resonant.

The Divine Comedy 5/10

I love the idea that you need a poet to guide you along the dark paths. But in such a renowned classic about the deepest subject matter, I was surprised by just how petty Dante is. As he travels through the Inferno, he picks out specific sinners and names them as his rivals, solemnly describing their sins and punishments. Enemy cities are denounced and it is implied that his own is favoured by heaven.

At times it is tedious. Sin after sin, level after level, the damned parade by in endless succession. It’s not until we approach the bottom that we get to the interesting characters. But after the tour takes in the giant Satan ice sculpture and pops out on the other side of Earth, we realize we’re only a third of the way through and the most famous part is behind us.

The climb of the mountain of purgatory he western vs the eastern aspects are explained in great detail. I did not care. Then at last we ascend to the heavens and this is the most boring of all. Just empty numerology, a list of sums, an accountant’s paradise.

Paradise Lost 8/10

First, this is a fantasy novel, not theology. The title screen would artfully admit that it is “inspired by the events in the Bible.” But it would make an exhilarating summer action movie. It is cinematic. The central character, Lucifer, is brilliantly written with notes of – not sympathy per se – but recognizable motivations and emotions.

Milton imagines the answers to all the fun Sunday School questions like how do angels fight? More interesting is how he explores the questions no one in any church I’ve been in asked, like the family relationship between Satan, Sin, and Death, and what happens when they argue (Sin, the mother, mediates).

Not every part is enthralling. There are long speeches, and a host of names, most beings are just another angel with a superpower in lieu of characteristics. They are mentioned and rarely heard from again.

Beowulf (Maria Dahvana Headley) 10/10

This is a slam poem, pulsing with rhythm and energy. If words alone can have charisma, this translation is soaked in it. It has the authentic ring of proper legend, the unabashed sincerity and yearning for great deeds. It’s a song, a muscular groove compelling my attention punctuated by audacious riffs that made me grin like a fool.

The jacket notes advertise it as a “feminist retelling”. This makes it sound like it will be a radical departure from the source material. It isn’t. It faithfully follows, as best I can tell, every plot point and character. The only thing radical is the astonishing power of language it unleashes. Is it feminist? I have no idea what that question even means. Beowulf is the quintessential macho storey, and Headley’s translation celebrates the hero’s swagger at every opportunity.

Okay, I suppose this translation gives some thought to how Grendel’s mother feels about her child’s sudden death. Is that feminist or just good storytelling? After all, interesting villains make for great stories.

Headley clearly loves Beowulf. She found every ember of life in it, and set it roaring into flame after centuries of stuffy, milquetoast translations. I had read a traditional one in university and shrugged; I felt that as a story, it had good bones but failed to captivate. Headley made me realise – insisted that I realise – that the plot points don’t make it art. The words make it art.

Short Stories (Chekhov) 3/10

Looking back much about these stories have faded, including the reason I was glad they were short. I think they were just full of dull talk, no particularly interesting or novel characters, no compelling ideas. The one I remember the best is the one I despised the most, where a man gives an improbably bad lecture on smoking to an audience so apathetic that they don’t provide any resistance as he veers off and complains about his wife.

Norse Mythology (Gaiman) 7/10

This is a fine collection of stories, curated from the Edda and reimagined. It has no subtly. It telegraphs the characters’ feelings and motivations so transparently that it’s occasionally embarrassing. Those moments feel like being spoken to like a child.

The characters have just been flattened a bit too much into stock Hollywood types, and the dialog is a bit corny. Still, they are good stories, so I can put up with a few sins. This would probably be perfect for the YA set.

Gothic

July 6

There was one savory moment of synchronicity. A summer storm had dimmed the afternoon sky to a sullen purple and I was a long way from home and just a little lost. Meanwhile Heathcliff was wreaking his awful revenge on the younger Cathy in that weatherbeaten patch of moors.

Pygmalion 7/10

Shaw’s most famous play, I believe, and also my introduction to him. Well met. It’s also an oddball in this list, a play, a comedy, and a tone that feels modern. Appraising these relics with 21st century sensibilities, I am somewhat alert to how a work treats the lower classes, women, and other races. Shaw acquits himself well here, as do many other authors of even earlier periods. It belies the tired defence that “it was a different time.” And there is really no excuse for artists today.

The Scarlet Letter 6/10

I admire it more in retrospect, but at the time I think I was just kind of sick of the characters well before the book ended. It starts off as a delicious mystery with deep, intriguing characters. But by the halfway point we’ve guessed all the novel’s secrets and have to patiently wait for Hester, Roger, and Arthur to finish tormenting each other and themselves. There are some depths that we only peer into, and that lingered in my mind. Pearl is sometimes strange and inexplicable, as is Hester’s return at the end.

It’s a bold novel about big ideas and big motivations: love, guilt, courage, revenge. I take its thesis to be that any correlation between religion and morality is accidental. I do recommend it even though it is too long on both ends – the preface alone was totally unnecessary and took hours.

The Allegory of the Cave 4/10

I realise that I’m panning the foundation of western philosophy. I’m not saying it wasn’t important and influential, or that it isn’t thought provoking. It’s a good metaphor and has several tasty ideas. I’m saying that my experience with it was marred by one mistake by Plato and one mistake by Tantor Media. First, the Socratic dialogue is a drag – Glaucon merely nods along every few sentences. Either have him argue and question or do without. In the second case, the audiobook was read by a dead ringer for Dr. Marvin Monroe from the Simpsons. What’s worse, he had a long and unconvincing preamble full of praise for American philosophers and businessmen.

The Prince 7/10

I liked it for the history. Machiavelli gives an abundance of examples for every point he develops. “Recent” examples of Italian kingdoms and duckies squabbling, more distant examples from Medieval Europe, and still more remote examples from Roman history.

As for whether the advice is immoral or correct or useful, I would say no, no, and no. It aims to be amoral, scientific, realistic. It may be all that in the sense that it has the tone if the philosophy of Realism, but I doubt it was ever very true. The explanations, like so much punditry today, sound like just so stories. For every factor Machiavelli considers, a thousand others go undescribed. And even for factors he discusses, it is dar easier to be right about direction than magnitude.

The Art of War 4/10

The same criticism as above, but missing both history and nuance. It’s essentially just hundreds of statements in the form of, “all else being equal, A is better than B.” This is very monotonous, and also doesn’t feel even potentially useful because the subject cannot be boiled down into a series of dilemmas, or even a flowchart for decision making.

This is the same trouble with improving at chess. The coach has told me to control the centre, put rooks on open files, prefer an open position if I have the two bishops, keep my king safe, put my knights on outposts, etc. But which is the best plan in this position? What is the optimal tradeoff between allowing my opponent to do these things and accomplishing them myself? There can be no answer. Being better at chess just means having a better intuition about what features of a position are more important. And so it is (I believe) for war. Sun Tzu notes that manoeuvring will tire your army and you should occupy advantageous ground and not be enticed off of it, but also that you should keep your army mobile so the enemy doesn’t know where you are.

Jane Eyre 8/10

The novel opens in the enormous shadow of Charles Dickens. A good orphan is maltreated and sent off to an awful school run by Mr. Brocklehurst, a Dickensian name and a dead ringer for the beadle from Oliver Twist or the school master from Nicholas Nickleby.

The difference is that Charlotte Brontë writes these characters earnestly and is less certain of right and wrong than the flippant Charles Dickens. Even Helen Burns is viewed ambivalently, whereas I feel she would have been written as a pitiful, pure saint by Dickens.

As Jane grows up, these comparisons fade away and I’m more tempted to see Mary Shelley and Poe. There is a mysterious creature, a dark secret, psychological melodrama, and many key plot points take place at night.

But ultimately it’s a love story. What struck me was how intellectually it is described. Jane and Rochester’s match is contrasted with others and its merits argued. It is passionate, but this is firmly secondary to its strict moral justification. The courtship is poetic without becoming sappy.

Both Mr. Rochester and Jane are susceptible to moonlight (who isn’t) but the principled Jane will not succumb to wuvvy duvvy wooing. Their repartie is sharp and fun and makes Jane a particularly memorable heroine. She is no beauty, she isn’t greatly “accomplished”, she has sense rather than wit and practicality rather than sensibility. But she is tough and resilient, self assured, and moral to the core.

There’s something to be said about that too. Religion is refracted through each character differently. The Christ-like Helen Burns on one end of the scale to the comic hypocrisy of Brocklehurst on the other are not so interesting, but in between, Rochester, St John, Jane, and Eliza have their own interpretations.

Rochester is almost irreligious, appealing to a spiritual law of kindness that he believes supersedes what he calls “man’s law” against bigamy, and is scornful of outward appearances of righteousness. He swears in church, calls Jane an elf and even dresses up as a fortune teller.

St John is dictatorial and yearns for danger and adventure, but needs it to believe that he is doing it for pure and noble causes. Becoming a missionary is the perfect cloak for his flaws. Who could refuse his demands and criticise the way he is devoting himself so unsparingly to religion? Only Jane.

Jane has a balance between St John’s fervour and Rochester’s spirituality. She rejects the hollow pretences of religious forms that hide cruelty or selfishness. But when she is tested, though her reason is spun round by Rochester’s arguments and appeals to kindness, she holds fast to the religious principles she grew up on.

The Diary of a Young Girl 8/10

What kept hitting me was how ordinary Anne and her family are. They are petty with the people they are cooped up with. they are kind when they can forget themselves, they are scared more by small incidents than the situation overall, they are depressed for weeks, they are happy in moments, they develop miniature wars and love affairs in their hearts, they forgive, they miss feelings from the past, they hope in the future, they follow the war on the news, they develop new interests, they are terribly bored, they resolve self improvement, they relapse, they are just like everyone I’ve ever known and me.

Heroes 8/10

Stephen Fry has long been a favourite. Here he reassembles the Greek legends concerning people. Not quite ordinary folks, you understand, but only up to the rank of demigod. Fry interprets these stories in his own affable, lettered style, with plenty of asides to tell us that we get some English word from such and such Greek character’s name. These tellings are a few notches more subtle than Gaiman’s Norse Sagas, but Fry still limits his characters to simple, unambiguous traits and motives, which I assume is still more nuance than the original legends had.

This is the chronological sequel to Mythos, which is about the Gods and Titans from the beginning of the cosmos, and for my money Heros has the better stories and more interesting characters.

Wuthering Heights 9/10

Unlike Jane Eyre, which took until act two to become a ghost story, this one starts off fully committed to that genre. It’s done really well. We meet our guide, the affable Mr. Lockwood, and almost immediately, we are plunged into a nightmarish mystery that seems supernatural, but very gradually becomes more and more explicable. By the end, we can almost sympathise with Heathcliff, despite his inhuman cruelty.

But I get ahead of myself. What a conception Heathcliff is. Hate and cruelty are pressed into him as a foundling until his defining trait is implacable malice. We get a brief sketch of how this happens – the partiality of Mr. Earnshaw nurses his pride into a monster, which is constantly stung and goaded by Hindley and the unkind instincts of most to his birth and sour countenance. But before he was brought to Wuthering Heights, much more must have been done to poison his character, and this is left to our imagination. He appears to arrive at the moors already well on the road to being a fiend.

It’s not necessary to give a logical, grounded explanation of his character, as Elliot/Evans might have. Emily Brontë, through Nelly Dean, places Heathcliff somewhere on the spectrum between human and monster. And why not? There must really be ghosts in this story; besides all the minor characters who insist on seeing them, Heathcliff’s final days wouldn’t make sense if it was some trope like a sudden nervous breakdown. Oh no, he was definitely being haunted by Cathy and he was in some kind of tantric state of agony and ecstasy until his soul was released.

All the characters are brilliant. Old Joseph gets a small role, but is such a bizarre addition to the story. And the others just accept that the servant is a mad, tyrannical prophet.

I also wonder about Nelly and how reliable she really is. From her own telling she is full of common sense and a desire to do right, but there are odd omissions and she can’t hide that she was occasionally manipulative (though always thoroughly justified by herself). Not that I think she is very wrong – she generally has sympathy for everyone (except Lynton but for the trick he played on her I can understand) and is happy for Catherine and Earnshaw at the end, so even if she isn’t the rock of righteousness that she appears on the surface, I think her narrative is probably a justifiable version of the truth.

Mythos 6/10

As mentioned, the first in the set. We cover the absurd creation myths with the child eating and the father murder and the titans raping their mothers and gods born out of thighs and on and on. Fry treats it all with affable charm. He finds what logic he can, and develops what little character is in the material, but there’s no disguising the chaos and arbitrariness of these legends without completely reimagining them.

Ivanhoe 8/10

I just enjoyed the heck out of the plot. It’s a pure adventure story. Set in the same time as Shakespeare’s histories, it was interesting to dwell in that period when the good solid common people are still basically Germanic, speaking Anglo-Saxon, while the elites are French.

This story really has it all. It mixes history and legend, borrowing the most interesting bits and weaving a sweeping tale that has suspense and romance, deliciously wicked villains and even an antihero. The big climax has both a witch trial and a jousting duel for all the marbles.

For my favourite character it’s a tossup between the loveable oaf Athelstane, who is only ever either obstinate or hungry, and the jester Wamba, who survives purely on his considerable wits and is as brave as any knight he meets.

A word on the unfortunate stereotype of jews in the form of Isaac – sigh – the moneylender. Pretty much everyone in this novel is a stereotype. The chivalrous knight. The arrogant king. The damsel in distress. Friggin Robin Hood shows up. I recognize that even among all the other tropes, reinforcing the moneylender stereotype is harmful. What saves it, I’d argue, is that Isaac is a good guy. It’s the baddies, including the sinister Knights Templar, who are antisemitic. Isaac is written sympathetically, generally does the right thing, and puts his daughter above himself. Speaking of Rebecca, she is probably the single noblest character in the whole novel, and that is saying a lot, stacked up against the titular Wilfrid of Ivanhoe, Richard the Lionhearted, Friar Tuck and Locksley, and even Wamba, the fool with a heart of gold.

Emma 7/10

The title character is simultaneously the most interesting and the most obnoxious Jane Austen heroine. She is very clever and often funny, a role that Austen usually reserves for men or her wicked characters. But she is also terribly conceited and her unfortunate friend Harriet pays the price.

The plot is just a series of matchmaking mishaps, but one incident in the middle stays with me. Emma, typically careless of the feelings of others, unintentionally wounds a poor chatterbox named Miss Bates. Proud and self absorbed though she is, Emma immediately repents and tries to make it up. That won me over. Until then I was worried I’d have to root for a vain and shallow heroine.

As always in Austen novels, the wise but boring gentleman marries the heroine in the end, but Emma’s wit and (charitably) self assurance make it an unusually equal match for the aptly named Mr. Knightly. Miss Bates, the spinster, was my favourite character though.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall 8/10

We start with a strange woman living in a ruined mansion, and very promising rumours that she is a witch. No such luck. There are several tiresome parts: long passages where the author makes her heroine recite entire pages or her personal and rather unorthodox theology. Outside those parts, the writing is absolutely first rate. I found the descriptions even more vivid than her sisters’ or really most other authors in this collection.

Our narrator Gilbert is in such puppy dog love with the mysterious woman, Helen, that it is alternately endearing and annoying. His pretty typical love story bookends the real meat of the novel: Helen’s diary explaining how she came to be a penniless single mother in a strange place.

There we meet her husband, a handsome, merry monster by the name of Arthur. Extraordinarily good humoured and vain, he is also an alcoholic in the exclusive company of several others. As his addiction deepens, a demon grows up. Mere selfishness becomes a burning need to satisfy his ego at any one else’s expense, and amusement at life twists and becomes amusement at the weak and the suffering. It’s a visceral portrait that must surely have come from some terrible personal acquaintance of Anne’s.

During Arthur’s descent, he casually relates a shocking act of cruelty to Helen, apparently thinking of it as just a funny anecdote. His sadistic cheerfulness at the harm he causes is really chilling, and we glimpse what is in store for Helen. When he does exercise his cruelty on her and their child, I believed it and I wonder how many other ladies of that period would recognize it from close experience.

Helen sacrifices much, acting on faith that it will work on Arthur and he can be redeemed in the end. So great is her religious fervour, that after she has risked everything to run away from him with their son – at a time when that was illegal for married women – when she hears he is dying from drink, she goes back and nurses him. That was beautiful, and the result – but what do you think? How does Anne end it: does Arthur repent, and does he live? What would be the true expression of these character’s and Anne’s own religious beliefs? And what would her 19th century audience be able to accept?

Northanger Abbey 8/10

My new favourite Jane Austen! Let me get my criticism out of the way: the ending is rushed right over. We are simply told, “all those loose ends? Oh, they get tied up neatly and now it’s happily ever after.” But that’s really my only complaint. The rest is a very funny send up of the novels of sensation and, to some extent, Austen’s repertoire..

Also, my favourite character from Emma returns, but this time she is called Mrs. Allen and she is even more delightfully oblivious. Our self-proclaimed heroine Catherine is in a difficult spot. She has promised to go on a walk with her Beau Henry, but her friends the Thorpes insist that she had promised to go see a castle with them. She looks to her dear guardian Mrs. Allen for assistance. Mrs. Allen is blissfully unaware. Catherine, desperate: what should I do? Mrs. Allen, placidly: just as you please, dear.

I think the main reason this is my favourite is that the “correct” suitor is finally a funny and lively person. He is self aware and satirical towards the social customs, isn’t a snob, and isn’t an old fossil. For once I feel I can root for the guy I like. Of course, I would like Henry because we share a vice. To put it charitably, I am quick to share my interests and gratified when I feel I have done it well. Maybe more accurately: I’m an overbearing know-it-all. Hence all of this..

Agnes Grey 5/10

I’m sorry, but Anne has to be one of the preachiest authors I’ve ever read, and this one indulges in that sin even more than Wildfell. What’s more, we have more governess stories here and I really feel I was adequately supplied with those by Jane Eyre. I know school teachers. I’ve tutored, which is kind of like being a governess on a small scale. I know the temptation to complain about students is very widespread. Reader, those complaints are not generally interesting to anyone else, and though Anne describes some truly wicked children and, what’s worse, clueless and mean parents, it isn’t very interesting here.

Sense and Sensibility 6/10

First, let’s identify our favourite Austen character. In this novel she has changed her name to Mrs. Jennings, and her mania is matchmaking, in contrast to Northanger’s Mrs. Allen (fashion) and Emma’s Miss Bates (unstoppable talker). Very good, but unfortunately we only get a concentrated dose of her near the end of the novel when the Dashwood’s stay in London to resolve the plot more quickly.

Now to the plot. It’s hard to ignore just how closely this hews to its alphabetical antecedent Pride & Prejudice. Again, the lesson seems: beware falling in love with those exciting bad boys, and three cheers for the old, boring, proper gentlemen. If Austen wasn’t such a fabulous wit, would she still be read at all?

Vanity Fair (abridged radio play) 5/10

Stephen Fry is back to narrate a much abridged version of Thackery’s masterpiece. The plot and characters seem interesting, and the production is excellent, but I would not recommend it. It’s like watching some highlights of an exciting match. You learn what happened and can appreciate the skill, but the suspense is gone, the emotional investment doesn’t exist, the connection to the players is severed. I have high hopes for the unabridged version when I find it.

Lady Susan 7/10

Oh ho ho now this is different. Leaving aside that it comprises only letters between the characters, it is also centred on a savvy, moderately wicked woman. A lot of Austen’s main characters are kind of bland, standing in as the everywoman or everyman for readers to relate to.

This time the novel centres on an alluring widow, Lady Susan, who sets out to earn the admiration of a naive young man named Reginald, mostly for the sport of it. His family warns him, but he’s down bad. We get letters from Susan, Reginald, Catherine (the one warning Regi) and others. Through these, we can piece together the actions and motives of the characters to some degree, but like all stories told by unreliable narrators, we’re never quite sure who is being honest, even with themselves.

Dramas in a typical Austen setting are a good candidate for this technique because of the expectation that everyone keep their feelings and any questionable motives tactfully out of sight. In company, high society maintains a careful facade of manners.

Lady Susan has a daughter, Frederica, a nice enough creature but not a schemer, and therefore devalued by her mother. We see flashes of Susan’s cruelty towards her daughter when Frederica rebels against a scheme to mary a very dumb but titled young man. This provides another example of how unnatural this woman is. I’m not sure I can think of another story where the main character is such a clearcut villain. Iago was certainly a pure villain, but you could argue that Othello was at least a co-star. I think Cassius was more of an antihero in Julius Caesar. Same for Raskolnikov, Ivan Ilyich, the Underground Man and other Russians we haven’t gotten to yet.

I’m sure the epistolary format wasn’t purely original, but I actually can’t think of any before this. The Moonstone, Dracula, and Screwtape come later. I can imagine it being done very poorly, but I don’t believe I’ve ever read one I disliked.

Far from the Madding Crowd 8/10

I had no idea what the title could possibly mean before I started (I still don’t), and I don’t think I’d even heard of Thomas Hardy, so I went in with far fewer expectations than for most books on this list. The result was a very pure experience that I’m grateful for. Hardy’s “Wessex novels” were extraordinarily popular in his day, but such are the changing fashions.

The warmth of this story felt so good. These are decent folks. Their lives are imbued with dignity by an instinctive honesty and kindness. They aren’t perfect – one fellow is a drinker, Boldwood the farmer is obsessive, Bathsheba the milkmaid cum landowner is vain – but no one wants to cause harm if they can at all help it. The exceptions are two: a dishonest bailiff who was caught and fired and lives in the margins of this story, and the main villain, Sergeant Troy.

Troy is charismatic and selfish, driven by ego and reckless with the hearts of others. He has remorse and conscience. This does not prevent him from being cruel. It does add depth and interest to a man who isn’t actually on the page all that much compared to the other main characters. I don’t know the word count, but it felt like he had fewer lines than many of the labourers who had little impact on the plot. That is probably what contributed to the positive vibes of this story – evil is often adventuring abroad or hiding out in another town, and until it moves into the farmhouse, we are treated to friendly conversation and the earthy concerns of bringing in the harvest and whether to have another small beer at the inn.

Writing as industrialization was invading the last bastions of Britain, Hardy was tapping into a growing sentiment about the good old ways being lost. It’s a cliché, and so too is pointing out that every generation has had the same worry for the next. But of course the times do change, and traditions fade or evolve, and the revolution of coal and steam put the pace of change into a new gear. So it’s a perfectly reasonable thing to try to immortalise a way of life before it alters beyond recognition.

I haven’t mentioned the protagonist, Gabriel Oak. He seems to be Hardy’s painting of the soul of Britain, which he insists is to be found out in the countryside. You can imagine the traits of a man whom Hardy has named Oak. Probably any adjective you like will apply here. Wessex stories are nostalgic, but was a world like this ever real? Maybe not this pure (what place has ever been hermetically sealed from the corrupting influences of politics and urbanism?) but that’s what novels are for. The fiction only makes it more pleasant.

Persuasion 7/10

The novel opens in very good style, by which I mean the first character we meet is my favourite Austen character. This time the Mrs. Allen/Miss Bates/Mrs. Jennings is none other than Sir Walter Eliot, father to our heroine. Gloriously vain and selfish, absurdly trivial like an Oscar Wilde character without the self awareness and wit. I was in love in an instant.

I think this is the clearest counter-example to my grand Austenian theory that she makes her heroines dependent and in need of the hero soon supplied. Here, Anne is clearly the superior being to Wentworth. She is cooler under pressure, more clear sighted, more virtuous. The reason she marries isn’t because she is foolish and wants correcting as Emma did. It isn’t because she is hopelessly naive like Catherine. No, Anne marries because she’s in love – by far the best reason in fiction.

Wentworth is alright, by the way. She’s not marrying down. So on the whole I’m more satisfied with the big picture plot here than in some others, although in my opinion it isn’t as brimful of sly irony as most of the other Austen titles. We get a deliciously rotten villain in the heir-presumptive William Eliot. A charming, scheming ruiner of women. But the way we find out is that we are simply told about it after the fact. It wasn’t naturally part of the story.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich 8/10

My first Russian, and as expected I found it at first to be mildly unpleasant, like very bitter beer. Ivan is a selfish, shallow, proud, middle aged man. He is obsessed with advancing his career. His marriage is loveless. The beginning felt slow, ironically, as Tolstoy takes us fairly briskly through Ivan’s life as a student and young civil servant. We see his general character forming and the probable arc of his life. He is a riser, using his gifts at networking to get better posts. All this would be a fairly ordinary biography.

Then he develops a complaint, a health issue, that the doctors disagree over and are powerless to cure. In spite of myself, I began to get interested. The observations of how people find ways of not seeing chronic illness, and the way we look for hope – in doctors, in religion, in other cases more or less similar, in the good days that disguise the overall downward trend – Tolstoy reveals them simply and clearly, with no great speeches or fanfare of anysort. These things are simply true, then and forever, and I don’t feel I can ever forget them.

Ivan’s promised death is not quick in coming. At times he feels better and deceives himself into thinking he will be fine, but never for long, and when it reasserts itself he is bitter and depressed. His wife takes a classic line of believing it would be all fine if he would just do what this doctor says exactly, and even when he does, she will not believe him. He’s playing it up to get even with her for some petty grudge. He’s too young to be fatally ill. She will not understand or accept the seriousness even as the end approaches.

Nothing has changed. Today, we blame sufferers, for not exercising enough, for eating the wrong things, for being poor. We look away from the sick, we shun disability. We offer platitudes and shallow sympathetic remarks. We still avoid acknowledging death. But death is promised in the title, and it will come for Ivan as it will for us.

For months, Ivan cannot accept that he will not survive this illness (or that even if he does, he will eventually have to die). He has no way to understand it. His suffering and mortality doesn’t fit with any other part of his life, devoted as it has been in always appearing to be perfectly proper.

Eventually an invalid confined to his couch, Ivan gives his low class servant Gerasim the unpleasant job of helping him with his bodily functions. Gerasim doesn’t complain and acts in sincere devotion to his master. It’s a new experience for Ivan, whose every other acquaintance is deeply selfish. Ivan asks him to stay with him through the nights, which must be long and terrible times of loneliness and agony.

Gerasim has no wise sermons for Ivan. He kneels so Ivan can elevate his legs on his servant’s shoulders for comfort. Ivan, his mind constantly circling the question Why stares at his servant’s face, this alien creature that has empathy for others, and the truth about his own life dawns on him.

Aesop’s Fables 5/10

A melange of nice little stories with tidy morals Very tiresome to listen to a dozen at a time. It’s The Art of War all over again. Proverbs, but with a trite little story attached, some a paragraph and some a page in length. Are they any good? They’re fine, I suppose. Unobjectionable, unexceptional. None of them struck me as a pearl of wisdom, perhaps because as cultural touchstones they are so worn, or perhaps because I’m the swine before whom one must not throw pearls (that moral comes from a different source), or because they are just not all that useful or profound.

A roll call to prove my point. Never give up. Choose the lesser of two evils. Be prepared. Think before you act. These are some weak ass morals.

But, you object, these are for children.

What person – especially a child! – will call to mind epigrams before deciding what to do? No one. Logically, how can anyone ever act on the “think before you act” one. Anyone who brings it to mind will have already done it by instinct first.

Look. They’re fine. Take them like sips of water every now and then, in between mouthfuls of more substantial fare. Or as the wolf might say to the crane, don’t always expect a reward from what you read.

The Brothers Karamazov (abridged play) 8/10

It’s a testament to how strong the material is that it can be extremely compelling after being translated to a new language, rewritten from novel to radio play, and have 93% of its length hacked off. Yet here it is, amputated so extensively as to be a head without its body, and yet it speaks with extraordinary power when it tells me the story of the inquisitor, or about the visit from the devil, or the trial. I’ll still try to find the full version.

Tess of the D’Urbervilles (abridged) 6/10

This one I’d heard of, and expectations were high after Madding. Perhaps because of that, and the abridged treatment, this was a minor letdown. Tess herself provides all the goodness I was looking forward to, but her story is truly bleak. That shouldn’t be a hit against a book. I’m just reporting that I did not wish it to be so. I hope to do justice to it by finding the full version and seeing how this painful struggle plays with all the characters, plot points, and exposition intended.

The Island of Doctor Moreau 7/10

This starts with one of those “I found this weird diary and here’s what it said” pre-ambles. It seems like a pointless waste of words. But it dawned on me that 1st person fiction might have been unusual for the time and the author felt they needed some explanation for why they weren’t narrating in a more typically omniscient manner. That’s my theory anyway.

This was a bit of a guilty pleasure. It’s dumb and grotesque but I’ll admit to having a macabre facination. Spoilers: Moreau, an ostracised vivisectionist, is doing some real messed up surgeries on animals that make them more human-like. They learn The Law (don’t walk on all fours, don’t eat meat etc) and they fear The House Of Pain where they were transformed.

We get a load of fake sciency mambo-jumbo drawing analogies to new medical discoveries and basically trying to give the premise some believability. If you know me, you can guess I was annoyed at this baloney, but really is it any different than lore in a fantasy novel? Anyway, once we get through Moreau’s hand waving and just go with the premise, it’s a fun and weird little adventure story.

The transformed animals are gradually reverting to their bestial state, Moreau’s assistant who has seen a little too much torture, takes to drink. And one of Moreau’s creations gets the drop on him, leaving our narrator in a tight spot. One downside to the frame narrative is there can be no suspense as to what happens since we know he must escape to complete his diary for us to find.

Summary: it’s goofy and I can’t really defend it, but I had fun.

Mansfield Park 4/10

Much of Jane Austen’s morality has not aged well: she seems to equate the aristocracy’s often absurd notions of correctness with real goodness. This attitude runs through all her novels to some extent, but it is at its most overt here. It’s so strong that I’m almost tempted to say she’s sending up the morality of the day with that patented Austen irony, but I don’t really believe it.

Our heroine Fanny is the archetypal wet blanket: mopey and self-righteous, an enemy of fun. She is sort of filling the role of orphan, although she is not one – her very much living family are just poor and gross. It’s like a rich snob’s version of David Copperfield. Is this device meant to elicit our sympathy (she is rather unfairly treated, particularly by a nasty aunt) or is it an extraordinarily subtle send-up of the device itself? If it is, I admit I never suspected it.

Having a main character who doesn’t enliven the pages is one sin, but even greater is the absence of my favourite type of Austen character. Sure, Mrs. Norris is exasperating and foolish, but that’s because of how nasty she is. It’s not endearing and funny like a Mrs. Allen or Sir Eliot.

Besides Yates the aspiring actor, the only other characters that add some life to this story are the “villains” Mary and Henry Crawford. These youths are truly out of control. Mary is clever and beautiful and loves an adventure. She tries to convince Edmund to be more ambitious in his career than a priest. Shocking, I know, but don’t worry. Edmund is a stick in the mud as well and resists her wicked love of fun because apparently that’s the proper thing to do. Henry, I’ll allow, is actually bad in running off with a married woman, since in that world, it does a lot more damage to her life than his. Basically I am at odds with the author, I’m quite sure. I’m always rooting against the ones she wants me to.

So what’s to like? Well, there is a play within the story and a temptation among the aristocrats to take a turn at acting. I do love this bit, but it’s asking a lot for this one subplot to lift such a long novel from mediocrity. What’s more, much of the good will Austen earns with the silly Yates character she throws away by again letting her stuffy morality step on the punchline. Sir Bertram arrives home and is met with this most improper display of amateur theatre in his drawing room. Great comic setup, except I just don’t think that’s the intention. Instead of landing the joke, Austen uses it as an example of how Fanny and Edmund were led into behaving improperly and how much pain it has caused their dear, noble father and how sorry they are. Keep in mind this grievous offence was that of playing at acting, and this is what positively floored the great Sir Bertram.